Trading Accounts

Trading Conditions

Financials

CFD Trading instruments

Don’t waste your time – keep track of how NFP affects the US dollar!

The ASIC policy prohibits us from providing services to clients in your region. Are you already registered with FBS and want to continue working in your Personal area?

Personal areaInformation is not investment advice

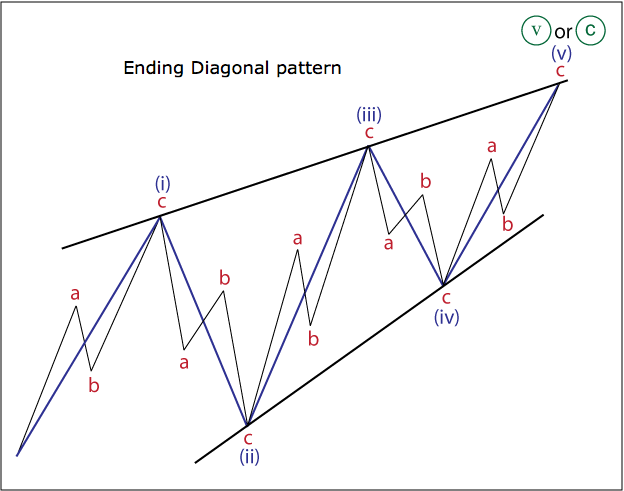

In the previous article, we discovered a leading diagonal, which acts as the beginning of an impulse or a zigzag. Today we’re going to examine a pattern that serves as the top-stone of an impulse (wave 5) or a zigzag (wave C), so let’s find out more about an ending diagonal pattern.

As you can see, the main difference from a leading diagonal is that the motive waves of an ending diagonal can be only zigzags. Sometimes we might face some ugly structures, but generally, the ending diagonal consists of zigzags. It’s also possible to sometimes have double zigzags in a position of the motive waves of an ending diagonal, but we’ll come back to this topic a little bit later when we go through all the correction patterns.

There are two variations of the ending diagonal: contracting and expanding. Mostly, the first wave of a contracting ending diagonal is the longest one, but the expanding pattern usually has the shortest first wave (in both cases, the third wave can’t be the shortest). Also, in real-time wave counting, an expanded ending diagonal is considered riskier than a contracting one.

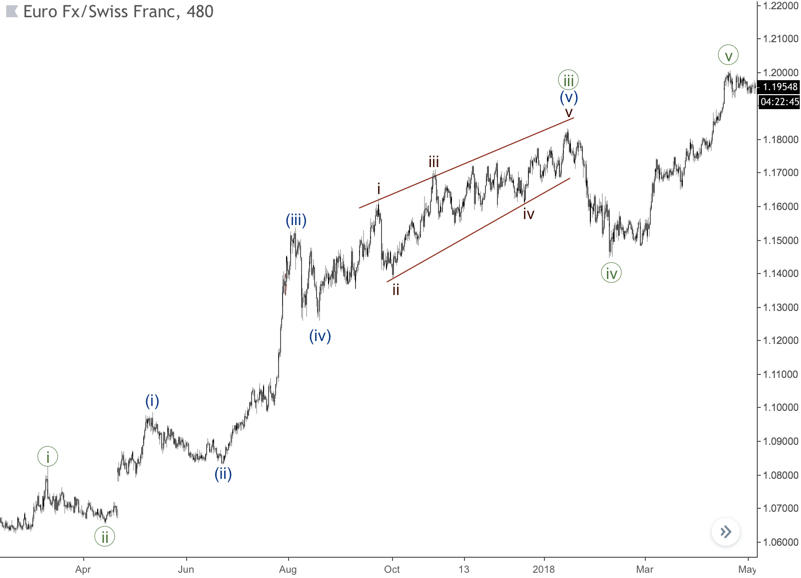

There’s a contracting ending diagonal in a position of the fifth wave on the chart below. As you can see, wave (i) is the longest and all the motive waves are zigzags. A pullback from the bottom diagonal led to a formation of a bullish impulse in wave (i).

However, sometimes the third wave of a contracting ending diagonal could be the longest. To be honest, this violates the rules from the book ‘Elliott Wave Principle: A Key to Market Behavior’, but the case happens in the markets quite often, so we should know what we could face.

The next chart represents a contracting ending diagonal in wave 5, but the third wave of the pattern is longer than the first wave and smaller than the fifth wave. So, there’s a contracting diagonal with the longest third wave.

There’s another thing we should know about the ending diagonal. Sometimes the price just can’t reach a line from waves one and three as shown in the example below. The first wave of this pattern is the longest (remember, the third wave can’t be the shortest anyway). Because this pattern was formed in a position of the fifth wave of the bigger third wave, then we had a downward correction (wave ((iv))) and another bullish impulse (wave ((v))).

It’s also possible to have a contracting pattern with the longest third wave, but a line from waves one and three remains untouched by wave five (check the next chart).

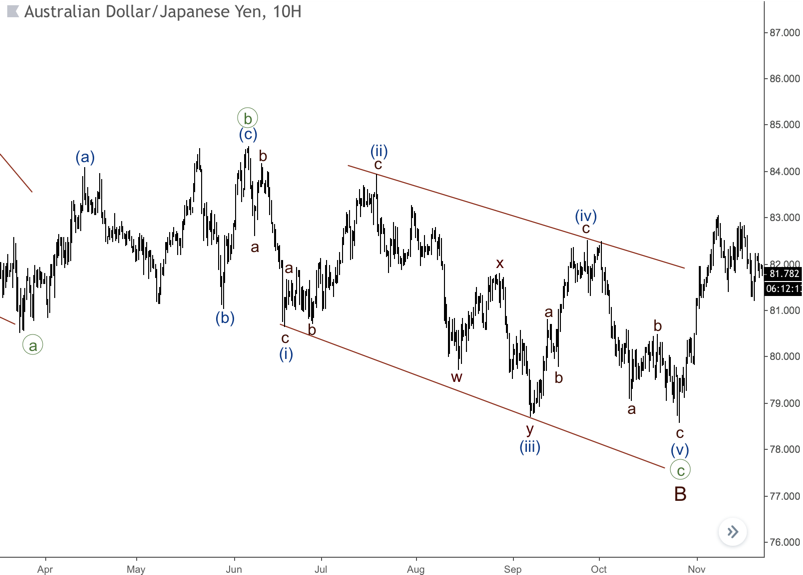

And here we are, there’s an expanding ending diagonal on the chart below. As you can see, the first wave is the longest. Also, the fifth wave hasn’t reached the pattern’s upper side. It’s a usual story for this type of ending diagonal.

There’s one more example of the expanding diagonal. The fifth wave here also hasn’t reached the bottom line of the pattern, but look at wave (iii): it is formed like a double zigzag. There’ll be another article about this correction formation, but for now, just remember that sometimes a motive wave of an ending diagonal could be not just a zigzag.

The ending diagonal is the end of an impulse or zigzag. This pattern consists of zigzags or more complex correction formations. The duration of a correction subsequent to a diagonal depends on a pattern’s position in the whole wave count.